How the Brain of a Maritime Pilot Works?

Rene Descartes in 17th century described animals as machines who reacted predictably according to external stimuli in their immediate environment in order to attain equilibrium or more practically to survive.

Three centuries later Ivan Pavlov, the famous Russian physiologist, went further.

In his famous “Dog experiment” he tried different stimuli on a dog to provoke his saliva secretion such as metronome, buzzer, bells, bubbling etc. and after each of such sounds, the dog was given food.

Now the dog’s brain was conditioned in such a fashion that as soon as he heard the sounds, he would salivate. His brain remembered the earlier experience and reacted accordingly so that the ingested food gets the required digestive juice. The dog knew that it was time that the bowl is served. Thus, his brain was conditioned to salivate without the sight of food, which was a natural process.

Surprisingly, humans also respond to the same stimuli. Most of us can look up at the sky and decide whether it will rain on a particular day and to carry an umbrella along. Humans have conditioned themselves to decide this.

Foto: Captain Matt Glass – Houston Pilot

Similarly, a maritime pilot during his training and throughout his career, gathers information from different situations and the biological neural network inside his brain records it, triggering the neural pathways once an identical situation arises. The brain automatically responds to this somewhat identical external stimulus. Counteractive measures pours out automatically and sometimes even unknowingly as there is hardly any time to think and respond.

Ship handling in an enclosed space like an impounded dock system entails a lot of nerve to overcome the fear of proximity or collision.

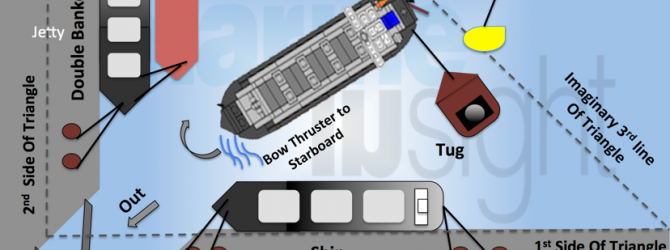

Suppose a 150m ship is being turned in a somewhat triangular space of a basin where any two arms are not more than 400m in length. The basin is cramped by doubly banked ship berthed on the arms, leaving the maritime pilot with a tricky situation.

Suppose the third arm is an imaginary line where you have the floating buoys (Refer Figure). The situation is palpable.

While the ship is being turned with the chief and second officers giving fore and aft clearance to the bridge, the pilot always uses this information along with those which he gathers following the shore transits.

The maritime pilot gives instantaneous orders determining the rudder-angle, the engine thrust and its direction, and the bow-thrusters or the stern-thrusters He orders the assisting tugs as well from time to time and he does all of these without spending much time to think. Sometimes he is facing the stern, but he has clear idea of his port and starboard sides and he gives orders flawlessly. His brain is conditioned to such situations so that he can anticipate the impending danger well in advance and the neurons of his cortex churns out the right order at the right time to avoid a hit.

With time the maritime pilot learns how to counter the effects of wind on the ship’s hull. With a high freeboard he will always be bodily adrift from the course. In enclosed harbor he may not always take the help of charts or other tools. Rather he follows shore objects as transit points and judges his position. A trained eye can even judge the SOG (Speed Over Ground) by seeing the reference points (be it a fixed crane, a light post , a tree, etc.).

Foto: Nasser Daefy

Moreover, each vessel has her own peculiarity. The pilot either remembers them if the vessel is on a regular line and visits the port occasionally, or else he acquaints himself with her behavior as fast as he can. His brain adapts to her peculiarities and ingrains them in its consciousness. He applies them almost immediately till the vessel is berthed. Though he has very little time, he has trained himself to adapt as quickly as possible to the varied situations he encounters day in and day out.

Thus, a pilot who is piloting in restricted space relies on his adaptability and with time his response becomes more accurate as he foresees a situation in advance. The synapses (a structure that allows a neuron to pass a chemical or electrical signal from one cell to the other) are more active in an adult brain than previously thought, and they rewire themselves in response to stimuli from the outside world.

Almost a decade ago a team of researchers from Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory led by neurobiologist Professor Karel Svoboda found out that “The brain operates with circuitry that is constantly changing in response to new demands.” Prof. Savoboda recently said to the BBC that “However, we think that the plasticity in the adult is quite different, and much more limited, than that observed in the developing brain.””Whereas in the developing brain the large-scale structure of neurons changes in response to experience, in the adult brain these structural changes are primarily local”, reported BBC. The research came out in the famous Nature magazine sometime in 2002.

Thus, as long as the maritime pilot keeps himself mentally agile and physically fit, he can earn his bread without considerable stress.

Unknowingly, his brain stands guard throughout his voyage, preventing obstructions and ensuring a safe passage.

Fonte: Marine Insight

Daniel Borges - 12 de dezembro de 2014, 14:28

Espetacular!